The ultimate goal for a software development methodology is to quickly develop and deliver high-quality software. That is, software with few bugs, which is performant and easy to work with in the future.

Several such methodologies prevail and are worth considering for the right project, among them test-driven development.

In this article I will explain and argue for why formal specification and algebraic specification are strong alternatives for the right project. This article does not fully explain either of those concepts, and assumes some background in technologies as well as theory, but aims to be generally useful for anyone learning about design methodologies.

To start, let's break down the 3 goals for a methodology mentioned above: Bugs, performance, and maintainability.

Goals

Bugs

Bugs are cases in which the actual behavior of your system differs from the expected behavior. However, your expectations are an abstract concept, and what we actually work with is specifications that you express in a variety of forms. This means that your specifications also need to be free from error.

Security bugs, also called vulnerabilities, are a subset of this in that some malicious behavior might give access or power to a user who attempts to acquire it. Security bugs are distinct from other bugs because of URGENCY, which we talk about below. It might not be urgent to stop a user from doing some fringe behavior and then getting to see a 404 page, but if they do the same behavior and get admin access, it's a big deal.

Performance

Performance can be thought of similar to bugs, in that you expect a system to meet some standard (Which, again, you have to be careful in specifying). That standard could look like the resources (Time, memory, gas) that it must consume to do a process. It might take into consideration the distribution of outcomes, such as that all transactions must clear in 10 seconds, or 95% of transactions must clear in 5 seconds.

While typically performance requirements should be expressed later than other specifications, if you're in a scenario in which performance requirements are crucial, establishing the viability of those pieces might need to be done before this more high-level analysis.

Specifying the conditions under which things occur is important, and requires a deeper understanding of what you're trying to build, for whom, and the future (Anything you're building will be used in the future, when the world will be different from your expectations). You can express these requirements in specifications and tests before you implement your design, and there's more to say about that. But this topic is less relevant to algebraic and formal specification, so it won't be our focus for this article.

Maintainability

Finally, we want our resulting product to be easy to work with. This means that when you or other developers try to read, change, or port your product, you can do so with a minimum of pain.

When you write tests or otherwise create specs, you are first figuring out what you expect the thing to do. You are also opening the conversation with others (On your team, partners, clients) of whether or not this understandable scenario that you've described should work as you say it should. It also gives an entrypoint for others to reason about changes in the future. If how something behaves should change, that becomes a concrete decision. There is a moment in which a developer changes the expected values in a test, submits that in a PR, and someone else approves it.

Feedback Loops

We also mentioned that we want this "quickly", which means that we want to express and reach clarity on our vision in as little time as possible. This process of communicating through a variety of forms, receiving feedback on the result, and using that feedback to influence the next step of the design is often called a feedback loop. Instead of moving straight towards implementing your vision of the design, you incrementally are expressing what you think is true about it, checking that everyone relevant agrees, tweaking it if something seems better, and iterating in that way up until a final product is delivered.

The time when you're writing tests is the best time to communicate and arrive at a unified vision with all parties involved. But more formal specifications can also do that for you, it's not just tests! Semantics for a formal language and algebraic specification can also bring you to unified vision with everyone involved.

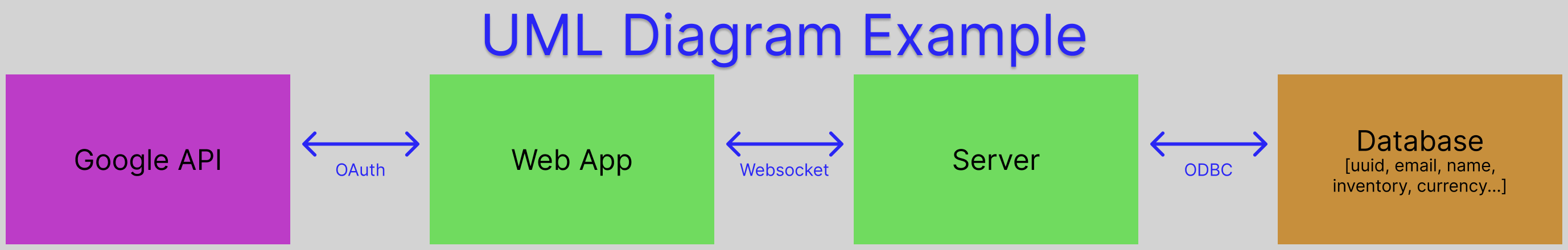

In the broader realm of specification, I also strongly encourage expressing your full design for what you're building in a UML diagram at this time. End-to-end tests cover what the full system is doing, integration test how those components interact, and unit tests for individual components. You may later find it supportive to introduce "unit" tests within a part of a component to ensure behavior of particular pieces as things grow, but you should first arrive at an understanding of how the system is working before you begin implementing.

It's okay to later realize that parts of this need to change, but:

- It's much more efficient to realize that early when your design is expressed in a diagram.

- That change should cascade down through from the diagram, to the tests, before finally you change the implementation.

- You get to see incremental results by expressing through diagrams, then specs, then implementation.

To clarify what I'm describing, each component is likely a separate github repo that in deployment is in a docker container, with another repo containing all repos in the project (Dependant on project). The interface between pieces is REST/websockets/file-access/etc.

The contribution of formal and algebraic specification less so applies to the uml diagram, and more to concretely expressing truths about the design. For example, algebraic precisely specifies the data and objects (And operations, which in some paradigms are "objects"). With that in hand and no code written, you can reason and confirm with everyone that the design makes sense before pouring engineer hours into it.

Test-Driven Development and Beyond

A development technique you've likely heard about but don't use is test-driven development. At its core it involves writing tests before you implement the code that you are testing. In practice, you could write unit tests, then implement the small black-boxes they test. Or you could write entire end-to-end tests, then integration tests, then the unit tests, then implement the smallest pieces. The ethos here is that you are first expressing what should happen before setting out to make it happen. This can be very helpful in clarifying those expectations for yourself, your teammates, and your ecosystem. Advocates for this design approach highlight how it creates good documentation, tightens the feedback loop, and encourages proper abstraction patterns in the implementations you end with.

Similarly, cryptography engineers often describe how a protocol works, publish that in some form, and then later the software engineers on a team implement it. You can imagine a similar process with algebraic specification in which you formally express the behavior of the data, including functions on that data (Which is more elegant in functional paradigms). This means, for example, specifying a language for all valid expressions, and a function which you are testing only accepting certain types of those expressions. It improves the feedback loop by, before any implementation has occurred, reasoning and discussion about the signatures involved in what will be built.

A similar example, creating new languages (DSL or otherwise) is a process in which you have some goals for what the system accomplishes. But all of the reasoning of what the underlying operations of the language are can be expressed and reasoned about in semantics before you need to start implementing any of it. These specifications are not the same thing as algebraic specification, but from seeing how statements compose you can arrive at clarity with your team, and easier determine what fringe-cases exist and what to test.

If you're unsure, or you're toying around, jumping into writing a compiler etc. is fine. But in all the places where you have concrete design goals, just describing the semantics is huge.

Below are the semantics for a very simple language (Both expressions and reductions, with environments assumed as seen in let binding)

EXPRESSIONS

e := n numbers

| x identifiers

| e1 + e2 addition

| e1 * e2 multiplication

| let x = e1 in e2 let binding

REDUCTIONS

n ⇓ n, x ⇓ x

e1 ⇓ a, e2 ⇓ b

_______________

e1 + e2 ⇓ a + b

e1 ⇓ a, e2 ⇓ b

_______________

e1 * e2 ⇓ a * b

e1 ⇓ a, e2[x / a] ⇓ b

_____________________

let x = e1 in e2 ⇓ b

Formal Specification

Formal specification is a variety of ways to express in mathematical terms what should be occurring in the program. This often uses Satisfiability or set theory to prove conclusively that the subject of your specification works in all cases.

You might, to give a defi example, express that for all source and destination addresses (Universal quantification) such that source has at least 100 coins, payment operation is valid. You would also further specify how the state of each wallet changes as a result of the transaction.

When using formal verification, many of the techniques involve some number of steps to either establish that, if I start in a valid state, I don't reach an invalid state within n steps, or attempt to prove or disprove Satisfiability of a statement in CNF within that same budget of steps. You can first formally specify what your program should do, then what you are verifying should become more clear to you.

Similar to broader testing methodology, you can separate out the areas of your code that require this level of rigor to ensure that your priorities are met.

You should still be aware that working in all cases relies on the abstractions that you've formed about the system still hold.

Algebraic Specification

Algebraic specification provides concrete descriptions of the data on which the software operates. They express the form of the components (Objects and operations) as well as what is included or not within a given formal language.

"Algebraic" here refers is the same as in "algebraic data types", and expresses that the types are both multiplicative (Tuples, also called records, are multiplicative since a tuple car = model * color * year is the product of each of the 3 types that compose it) and additive (Variants are additive since the set of a variant is the sum of each of its possibilities animal = | dog | cat | bird). You can reason about what these should be and have that conversation early, and if it's appropriately restrictive, your type-checker saves you from composing in any ways that are invalid. That means you won't have to write awkward tests on the types of your inputs that prevent runtime errors.

Many modern languages support ADTs, but even ones that don't have the option to express the interface (Trait in Rust) of a class before providing the implementation. You can take advantage of this to first spec that out before implementing it.

We benefit greatly from type-checkers being supported, in-use, and understood by developers. This makes it less of a lift to use this methodology, and when your specifications are violated the feedback the engineer gets is in a form that they're likely used to. It also means that any compilation of your program is guaranteed to have met the ontologies that you have expressed.

Other systems, such as static analysis to determine whether your types are as tight as they could be, can further support this step of development. This also draws from existing well-established theory around sets and types.

type zero = unit

type `n succ = unit -> `n

(* Example of a balanced binary tree in ocaml, using Peano numbers for depth *)

type (`depth, `a) bbtree =

| Leaf : (zero, `a) bbtree

| BranchBalanced : `a -> (`depth, `a) bbtree -> (`depth, `a) bbtree -> (`depth succ, `a) bbtree

| BranchMoreLeft : `a -> (`depth, `a) bbtree -> (`depth succ, `a) bbtree -> (`depth succ succ, `a) bbtree

| BranchMoreRight : `a -> (`depth succ, `a) bbtree -> (`depth, `a) bbtree -> (`depth succ succ, `a) bbtreeModel Versus Reality

A useful concept in software is the idea of abstraction, in which we don't have to hold all of the details of the reality of something in our head. Instead, we imagine it to be a simpler thing, which is easier to conceptualize because it matches some real world thing or concept that we spent many hours thinking about.

The saying "the finger pointing to the moon" illustrates that the signifier for something (The pointing finger) is not the reality of that thing (The moon).

The issue that we run into, however, is that the reality is often complicated. We have layer after layer, starting with electric current through metal, that all pretends that its model of reality is the true reality.

Some subtle ways in which your model doesn't match reality could include:

- A method call has a side-effect

- Asynchronous code that depends on your scheduler implementation

- Underlying data structures that have certain bounds / requirements. These might cause major issue only rarely, in fringe cases, or when you change something about the underlying architecture. Making them especially difficult to detect.

Some modern languages, and modern versions of existing languages, strive to prevent situations like these. Some of the ways they do so include being strongly-typed, defaulting to immutable data, borrowing-checkers, and concurrency guarantees. When using languages with these features, your model matching the reality as tightly as possible becomes much easier.

Accurately viewing the world is hard, but then communicating that vision to someone else and them getting it is even harder. Communication of a design before its created, to ensure that it matches what everyone wants, becomes a very tricky proposition. For that reason, techniques such as diagrams, visuals, and precise mathematical expression all becomes crucial based on the circumstance and audience.

Making Educated Tradeoffs

Broadly, the main question when taking any action is of valuation, and life is a continuous and unavoidable experience of taking action. That question of valuation, or how much something is worth, also gets called risk-assessment, and is a crucial consideration when deciding between the tradeoffs of arriving at clarity, ensuring that what's created works, and generating more. While it's often useful for engineers to tunnel-vision on one piece of a system, the broader process must be compelled by a holistic lens. Coming to understand what your subconscious reaches for - be it planning, creating, or sharing - is critical for you to be the arbiter and not land in ruin.

Formal verification is inherently a balancing of resources versus risk in that you run it for some number of steps in an attempt to show things about the existence or nonexistence of unwanted behavior. For example, you start in a state in a finite state machine, then run for 100 steps to see if you ever enter an invalid state. As you design and run these tests, you are balancing perceived risk with actual loss of resources associated with having a computer run your test for some number of clock-cycles. These sorts of trade-offs happen all the time, and ideally it isn't just the engineer mind that provides input into their rationality.

The valuation of creation is trickier to account for, since exploratory design is necessarily a situation in which you, to some degree, don't know what to expect. But just like a ship setting sail may not know for certain when it will land, the right tools can make the journey much safer.

Broader Toolset

When deciding on the testing and design methodology that is right for you, there are many other tools and techniques in the broader thought-space that are worth knowing about. Beyond the commonly accepted ones, I also argue that ANY developer tool is effective bug mitigation.

These are some of the tools in the broader context, which are worth knowing about:

- Fuzzing

- Coverage Reports

- Audits (And CR)

- Field Testing (AB testing, Canary, relying on users reporting errors)

Fuzzing

Fuzzing is the process of supplying random inputs to a program to find bugs. In this case, the expected versus actual behavior has to be thinner, since developers may not know the value that a given input should return. They would, however, be able to categorize stack-overflow as an unwanted behavior. Fuzzing has become more well-known in the last decade - Shellshock was discovered through fuzzing, for example.

Coverage Reports

Coverage reports give you information about what portion of your code is being touched by a suite of tests, to ensure that bugs that occur on a given control-flow branch don't go unnoticed. It is complementary to conventional automated testing, and informs you the "quality" of your testing, and where you should add more tests.

Audits and Code-Review

Audits are when other professionals, especially ones with specialized knowledge, review, grade, and suggest changes to your codebase. It's usually done topically based on what is most important (For example, the code that works with high-security resources get audited, or a method whose runtime is crucial to your business). This gets used most in niche or developing fields, in which a team might not have the specialized understanding to reason or make low-bug code. In some ways, this is just another flavor of code-review.

Field Testing

I use field-testing here to talk about a broad category of things that happen in the real world and "test" your code. Having a library be around and in use for a decade gives you some faith in its safety since any niche bugs will likely be experienced, complained about, and resolved during that time. AB testing is less about unexpected behavior, and more seeing which of 2 designs, when given to a user, they "prefer" (Respond in the way you want to). Canary testing means pushing to a slice of the general audience a piece of code which may fail, and seeing if it does (Canary in a coal mine style). All of these emphasize the fact that the lifecycle of code includes when its in use, and the greater ecosystem is best not ignored.

Any Developer Tool

Finally, I claim that ANY developer tool is a mitigator of bugs. Developer tools cause greater clarity and reasoning with which the engineer can now conceptualize the system. They allow understanding to better be shared and persist, and take away foot-guns. At the end of the day, development is all about harm-reduction. Static analysis tools like linters, which have been created from developers who work with a particular piece of tech (Language, use-case) precisely in order to warn about when you are doing something dangerous or stupid. You are benefitting from all those who came before you. Language design is similar, both in the ideals of how safe a language is, and the realities of how safe it is when you get it in the hands of developers.

Final Thoughts

While this article is exploratory in many ways, I want to emphasize a few key results that I think fall out from its considerations:

- Communicating and arriving at clarity of vision is crucial in a development process, and algebraic + formal specification are both good ways to do that.

- Using techniques that have decades of theory behind them, and have familiar analogs for most developers (Type-checkers) makes it much easier to integrate into your team.

- Balancing risk is a constant part of design, and testing + specification lets you engage with that more directly.

If parts of this article are intriguing, and you'd like to talk more, I'd love to open up that conversation. As always, the best way to learn is to take it out for a spin and play with it. It's an exciting time when much of this methodology is developed enough to be viable, but still largely underexplored.

Share this article: